Girish Karnad: An Unconventional Colossus

Text: G Ulaganathan, a senior journalist and dance critic based in Bengaluru

Pics: Sangeet Natak Akademi Library

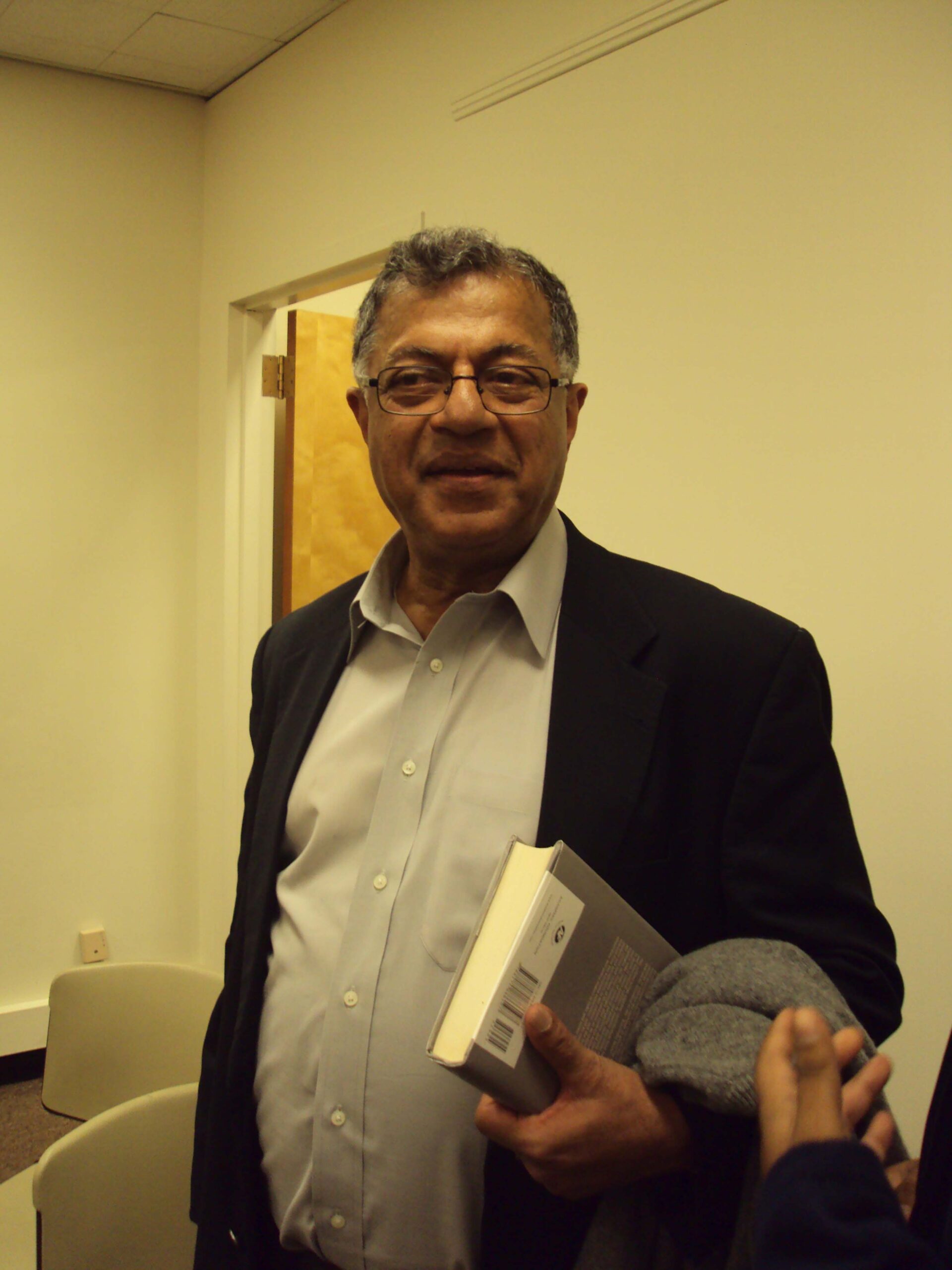

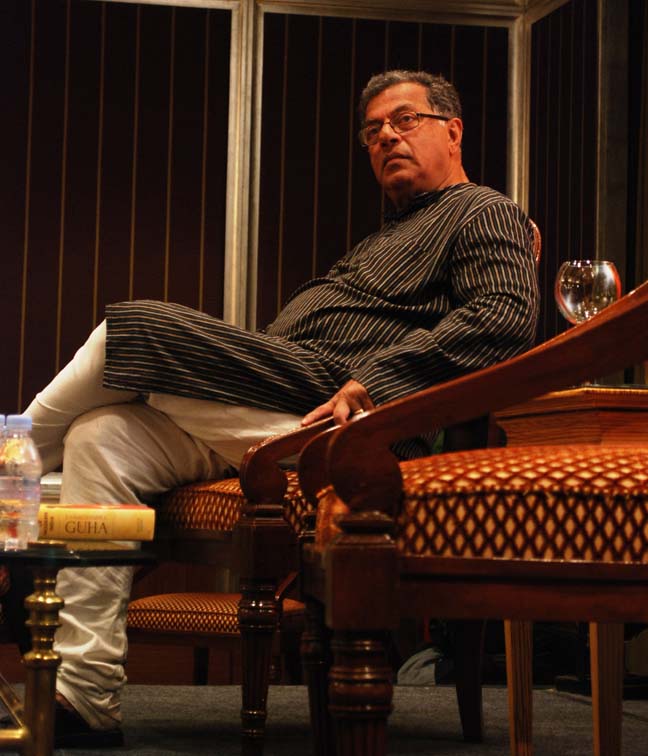

As one walks into the beautiful amphitheatre Ranga Shankara in J. P. Nagar in Bengaluru, a booming voice welcomes you with the words, “Yellarigu Namaskara” and advises us “Nimma mobile phones switch off maadi.”This is repeated in Kannada, Hindi and English. We immediately recognise the voice and follow the instructions. The voice belongs to none other than the multi-faceted Girish Karnad. The legend passed away last month, but his enormous legacy, along with these sweet words, will linger forever.How does one classify him? Veteran actor, playwright, film director, an author, a Rhodes Scholar, a strong dissenting voice against right-wing activism, and more than anything else, a proud Kannadiga who was passionate about his language and culture.Think of the Kannada theatre, the first name that comes to mind is Girish Karnad. For the past 50 years, he had used history and mythology to express urban truths in Kannada.Girish Raghunath Karnad, born in Matheran in Maharashtra, was a talented film-maker, a person of many accomplishments and interests. His plays hold a mirror to the problems and challenges of contemporary life and endeavour to forge a link between the past and the present.

His plays act as a medium to communicate his own, independent and original feelings, thoughts and interpretations.He was so talented that he used to translate into English his own plays, written mostly in Kannada. After his initial studies and graduation in 1958 from the Karnataka University, he became a Rhodes Scholar and studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the Oxford University from 1960 to 1963.

His first play, , written in 1961, focuses on the mythological king by the same name. In this play, historical themes are beautifully clubbed.

His next play, Tughlaq, written in 1964, centred on the 14th century Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq. Then followed the brilliant Samskara in 1970 which was made into a memorable and award-winning film.

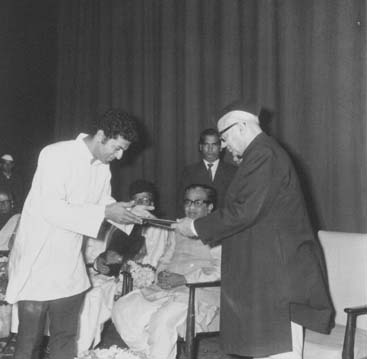

Samskara was directed by Pattabhirama Reddy, and Karnad wrote the screenplay and also made his debut as a lead actor. The film won the President’s Golden Lotus Award for Kannada Cinema. A novel written by his close friend and associate U.R. Ananthamurthy inspired the movie.

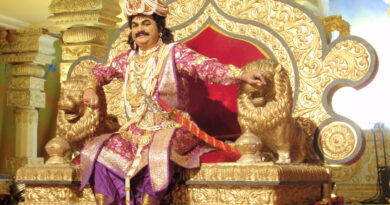

As a child, he went to several Natak Mandalis with his parents, who were also fond of the performing arts. There, he learnt about performing arts and Yakshagana, the traditional theatre form of Karnataka, and began to grow as an artist.

Most of his plays, especially Hayavadana (1971), were widely recognised as among the most important plays of post-Independence India.

His other well-known films in Kannada include Tabbaliyu Neenade Magane (1977) and Ondaanondu Kaaladalli (1978). In Hindi, he directed Utsav (1984) which was an adaptation of Shudraka’s fourth-century Sanskrit play Mrichchakatika. Girish Karnad also showcased unhappy contemporary marriage imagery drawn from Kannada folk tales in the play Nagamandala (1988).

An interesting fact, not known to many, is that he had also lent his voice to the autobiography of former President APJ Abdul Kalam, ‘Wings of Fire’, when it was turned into an audiobook.He served as the director of the Nehru Centre and as a minister of culture from 2000 to 2003 in the Indian High Commission, London. But those were not his happy years as he told some of us later. “There was very little creative work I could do apart from organising and attending official functions. So I gave it up and came back to my roots.”He won the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi award for his play Hayavadana and the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya award in 1978.

He also had a brief stint as chairman of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.But, two positions he enjoyed were as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1987-88 and as director of the Film and Television Institute of India.When an unknown, aspiring actor Om Puri wanted to join FTII those days, the interview committee rejected him saying he was dark and did not have the face to become an actor. But, Girish Karnad put his foot down and ensured that Om Puri was selected. The rest is history.

He had started writing his autobiography but could not go beyond the first half of his life. He once said it was like “Ardhakathanaka”, written by a Jain trader called Banarasidas of Agra in the 17th century. This precocious trader had stopped his life-story, arguably first-of-its-kind in Indian literary history, at fifty, assuming that the full lifespan is one hundred years.

“I am now 73 (in 2011). The last event in this autobiography is when I walked out of the Film and Television Institute of India. I was 37 then,” Karnad writes.

Karnad’s father worked and retired as a doctor (specialised in post-mortems) in Sirsi and Dharwad. His mother was a trained nurse and a young widow with a child. She became his father’s second wife, after ‘sensationally’ living with him for five years.

This forms the dramatic beginning of Karnad’s autobiography. “My first encounters with pain, tragedy, and hilarity of life happened in the Sirsi hospital compound where we lived. A lot of things would happen there unexpectedly and theatrically, but continuously. There was nobody to stop me, my sister Leena and children of our age in the compound, from being premature bystanders to all this. However, we stayed away from the corner post-mortem room. Besides the scary whisper about bodies lying there, because of either suicide, or an accident, or a murder reaching our little ears, the mental image of our father inside, tearing open the bodies and examining them, prevented us from peeping in.”

Since the shadow of death stalked his childhood, Karnad says dead bodies ceased to evoke any emotion in him. But, he believed in ghosts. It is these ghosts, through his imagination, that perhaps entered his historical and mythological plays, be it his first play Yayati, or Tughlaq that followed. And, he was able to brilliantly describe the transposition in Hayavadana or the split personality in Nagamandala.

Karnad’s strident public position on liberal traditions, communal harmony and cultural diversity perhaps had its formative years in Sirsi. There was a church near his house, where the service was conducted in Konkani, Karnad’s mother tongue.

He, along with other Hindu children, used to visit the church every Sunday and take part in the service and listen to stories from the Bible. Karnad’s family was from a high-caste Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin community, the same as Deepika Padukone, Shyam Benegal and Guru Dutt.

When the chief pontiff of the Chitrapur Saraswats visited Karnad’s house in Sirsi, there was no big chair befitting his status. The family borrowed a chair from the nearby church, which was reserved for the Bishop. “The church had no problem that the chair was being borrowed to seat a Hindu religious head,” said Karnad.

This innocence and accommodation have largely gone missing in India’s small and big towns today, he regretted.There is also something else that is missing in towns like Sirsi. According to Karnad, it is the romance that darkness brought in the absence of electricity lines. And, the plethora of stories that were tucked in every crevice, corner, lane and bylane.The mind had the freedom to work its own independent cosmos. “In the hospital-house and later the Rayarapet house where we lived in Sirsi for a total of ten years, electricity had not made an entry. We lived experiencing darkness, in fact, it would be more appropriate to say that we grew up relishing it. In that darkness, the light came in hundred different ways to provoke our senses,” he writes.The next town, Dharwad, was where his intellectual trajectory took shape. He got passionate about literature and philosophy, aspired to be a poet but ended up being a playwright.A small publisher, Manohara Granthamala, housed in a small attic in Dharwad, mentored his extraordinary talent, and published all his works from the beginning to the end, including the Kannada autobiography.

Despite his global success, his loyalty to the Joshi family that runs the publishing firm never wavered. Incidentally, the Joshis are close relatives of Hindustani music legend Bhimsen Joshi.

About his student years in Dharwad, Karnad says: “As a student of mathematics, initially, I was not very loyal to the subject.

It was to score high marks that I had taken it up. But when I got immersed in it as months passed, I began to understand its rhythm, its pitch, its progression, and crescendo. Its beauty danced in front of my eyes.

A character in Aldous Huxley’s novel weeps at the beauty of the Binomial Theorem. There is nothing surprising about this reaction when numbers unravel their mystical attributes wave by wave, branch by branch.”

“I realised the impact that mathematics had on me when I started writing Tughlaq in Oxford. I solved the structural issues like I would while working on theorems. I first figured out what internal network and relationship different aspects and characters of the play had, what its balance at various points was, and what happens to that balance if the play progresses in a certain direction, just like it happens in a theorem. The technical training I needed to write plays came from mathematics.”

Why did he give up the glamorous life in England and come back to Bengaluru?

Says Sugata Srinivasaraju, a senior journalist and author: In a rare sentimental expression, Karnad writes: “At that point, after having experienced alienation of various sorts in the English society, the innocence about talent getting a huge reception, and success being assured in England, had somewhat dissolved in my head. I asked myself if I would ever get the near maternal affection with which the Kannada intellectual world had celebrated my first play?”

“I concluded that my decision to settle down abroad was not only vacuous but also self-defeating… So, I landed up in India where a cultural resurgence had begun. Although the country’s economy was struggling, a grand new spirit was being forged in the world of films, literature and theatre. It was opening up doors to a new era, and it beckoned me. It is this infinite opportunity that I had walked into.”

Karnad was the conscience of the whole country, not of just Kannada and Karnataka. Through his various characters, he brought to life the nature of human beings and led his life as reflected in his writings.

Says Kavitha Lankesh, “I still remember that when Hayavadana was getting ready to be staged, a huge elephant and masks were prepared in our house. Those were the days when my father P. Lankesh, Karnad, Ananthamurthy, Tejaswi would all wait for each other’s next writings. Discussions, healthy criticism and sometimes envy, were common.”

Her sister, the late Gauri Lankesh and Karnad, were fierce supporters of the Forum for Communal Harmony. Gauri and he travelled together and were even jailed in Chikmagaluru, fighting for Bababudan Giri, one of Gauri’s first causes.On Gauri’s first death anniversary too, he said he would come but not speak. He came with a board hanging on his chest that said ‘Me Too Urban Naxal’ that spoke volumes and resonated across the country.It was said that even Karnad was on the hit-list. Yet, like Gauri, he refused security and lived his life—fighting communalism and fascism and stood for the minority and the downtrodden till his last breath.Unlike many other writers of our times, Karnad had no personal political ambitions. His political views were expressed through his literary works.

“Thinkers and writers like Girish Karnad who grew up in a plural, tolerant India, will be missed, and now is the moment we need them the most,” says Nabaneeta Dev Sen, an award-winning poet, novelist and academic.Girish Karnad did not create a spectacle out of his death. He had scripted it that way.

There were no politicians with wreaths, no state funeral, no winding queues of admirers, no television crews with a breathless, uninformed commentary, and there were no priests, no chants, no rituals.