The Margazhi Music and Dance Season

Text: ‘Nritya Kalanidhi’ Lakshmi Viswanathan

When Chennai was Madras, the migrant population from the temple towns of Tamil Nadu brought their customs and music to the city. The temples attracted musicians who sang Bhajans at dawn around these temples of Madras as part of the holy month of Margazhi. It was a tribute to the saints in this holy month, and the Thiruppavai songs of Saint Andal were sung with fervour as they are to this day.

When the British dominated Madras, the “season”, which meant celebrating Christmas and New Year with a vacation, became the most anticipated break for lawyers, government employees and professionals. It was this holiday spirit which inspired a group of Indian music enthusiasts to organise a conference of music with experts in old Madras which even had a nip in the air with the end of the seasonal monsoon. The conference of 1927 gradually became a festival and coincided with the Congress party meet, an important event in those pre-independence days. The first real music festival was held in 1929, and with it was born the idea of an institution — The Music Academy — to conduct annual festivals. Another equally old institution was born — the Indian Fine Arts Society. The elite of Madras congregated in North Madras where halls were available to listen to Carnatic musicians, mostly male who came from the Cauvery delta region of Tamil Nadu, having seriously taken to the art under the tutelage of great composers and Gurus.

The Bhakti songs of Tyagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar and Syama Sastry, as well as Tamil composers like Muthu Tandavar, Marimuttha Pillai and others, found eager listeners among intellectuals who were advocates in the Madras High Court and had a passion for classical music. Several decades and after many a social change, today we have innumerable sabhas organising December music and dance festivals catering to every type of audience in Chennai. It is estimated that at least a thousand concerts take place from dawn to midnight around the city, with an equal number of eager artists keen to get a name and prove their talent. There may not be big audiences in all the venues but there is an atmosphere of the joy of music and dance everywhere with many visitors nostalgically going around Chennai, listening to their favourite singers or seeing star dancers. Many visitors from other cities marvel that in Chennai, festivals are ticketed and people are willing to book at any cost. However, most of the day concerts are free and attract interested audiences. Artists who are not famous crave for an opportunity while established performers carefully plan their dozen appearances. Child prodigies are launched in this season with the hope of recognition. Veterans who are Padma Bhushan and Sangita Kalanidhis (the so-called Nobel of Carnatic music awarded by the Music Academy) such as vocalist Trissur Ramachandran and TN Krishnan, the violin vidwan, perform in the morning sessions and are big draws. They offer the essence of classical music and bring back memories of great Gurus and give a taste of an authentic style which is often not found in the new aspirants.

The iconic names of Carnatic music like M.S. Subbulakshmi, D.K. Pattammal, M.L. Vasanthakumari, Semmangudi Srinivas Iyer, Lalgudi Jayaraman, Maharajapuram Santhanam, Balamuralikrishna, to name a few, are not with us anymore. I recall attending all their concerts with anticipation and excitement. To take their place many new singers are seen on stage sincerely presenting their best. Many young talents are introduced each year, but the audience does not increase in the same proportion. One can say that this music appeals to a minority, but is kept alive because of its intrinsic worth as classical music. Seniors are often heard saying: “To listen to Carnatic music and appreciate it, you must reach a mature age, and understand the spiritual content as well as Raga Bhava. Only experience will make a mature Rasika.”

The scene in Margazhi was predominantly music for many years. There was a rare inclusion of dance by a few well-known dancers like Balasaraswathi or Kamala. Bharatanatyam was still in its nascent stage as a popular art. But all that changed and today we have thousands of dancers performing, teaching and aspiring to make a mark during the season. The first important dance festival was started in the seventies at Sri Krishna Gana Sabha, and a decade later it was accompanied by a Natya Kala Conference, as well as a title and honours for a classical dancer. I recall with nostalgia being honoured with the title ‘Nritya Choodamani’, with Balasaraswathi, Vyjayantimala, and M.L. Vasanthakumari felicitating me. I was the convener of the Natya Kala Conference in 1984 and 1985. Those were glorious days for dance because the conference took a national colour with the participation of national artists cum Gurus like Kelucharan Mohapatra, Birju Maharaj and Rajkumar Singhajit Singh to name a few. Audiences were made familiar with many styles and many stalwarts enjoyed coming to Madras where they were welcomed with enthusiasm along with their famous disciples.

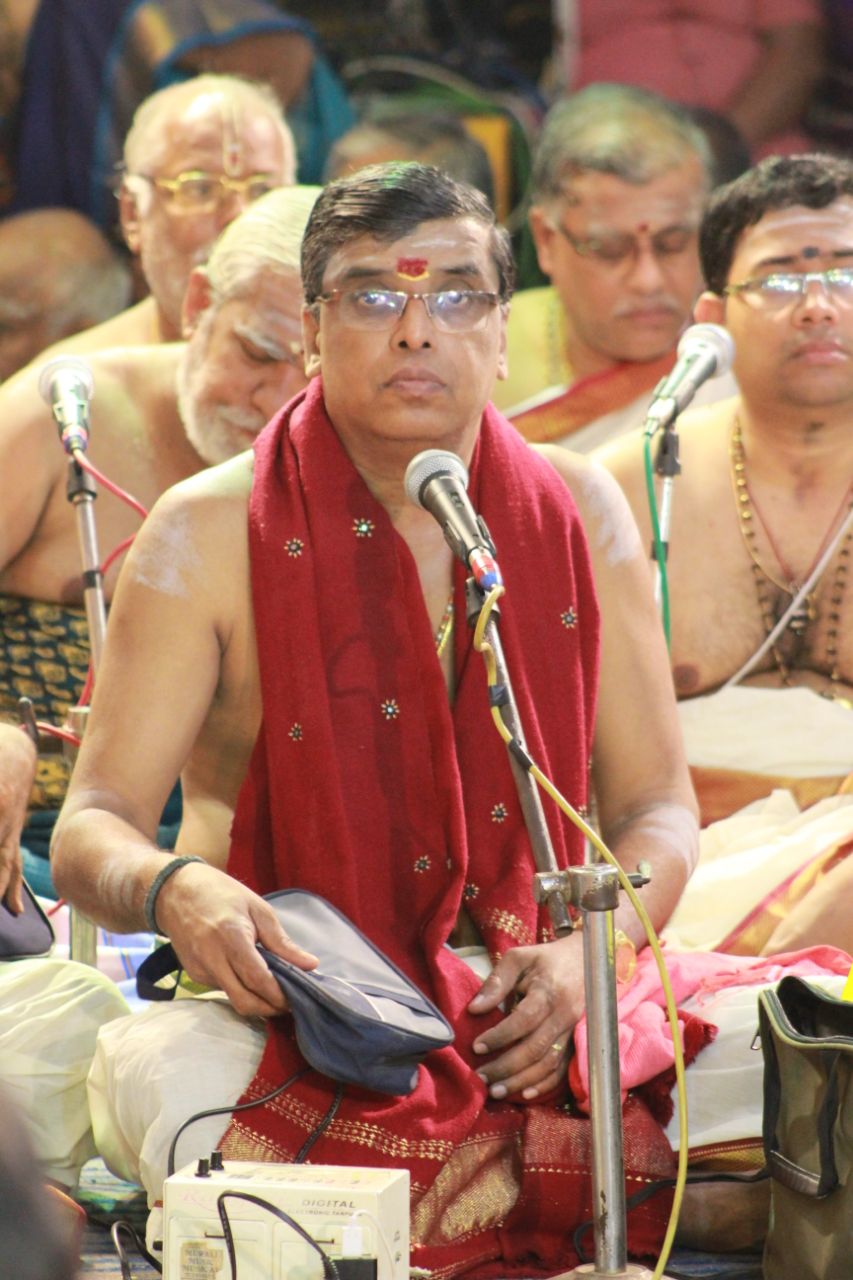

Harikatha discourses, Namasankeerthanam group singing, and lectures have their own enthusiastic crowds during Margazhi. Sometimes they outnumber the attendance in music and dance concerts. It just shows that our people associate the month of Margazhi with essentially sacred music. They feel fulfilled in these popular community events. It is a throwback to the customs which prevailed for long in the rural temple towns of Tanjore. If music and dance find the right expression as sacred arts they are to be lauded. Margazhi is after all a sacred month meant for dedication and prayer!