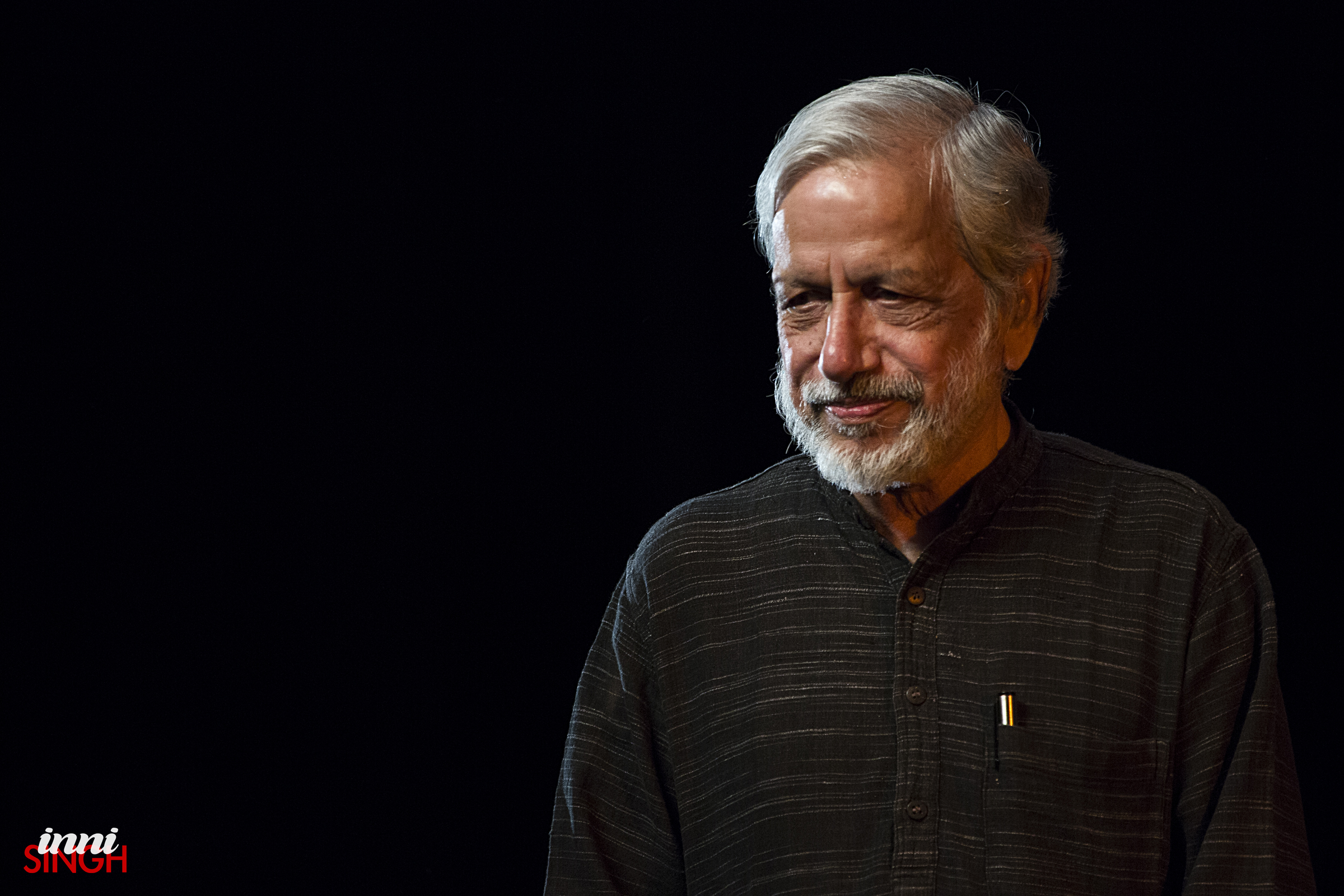

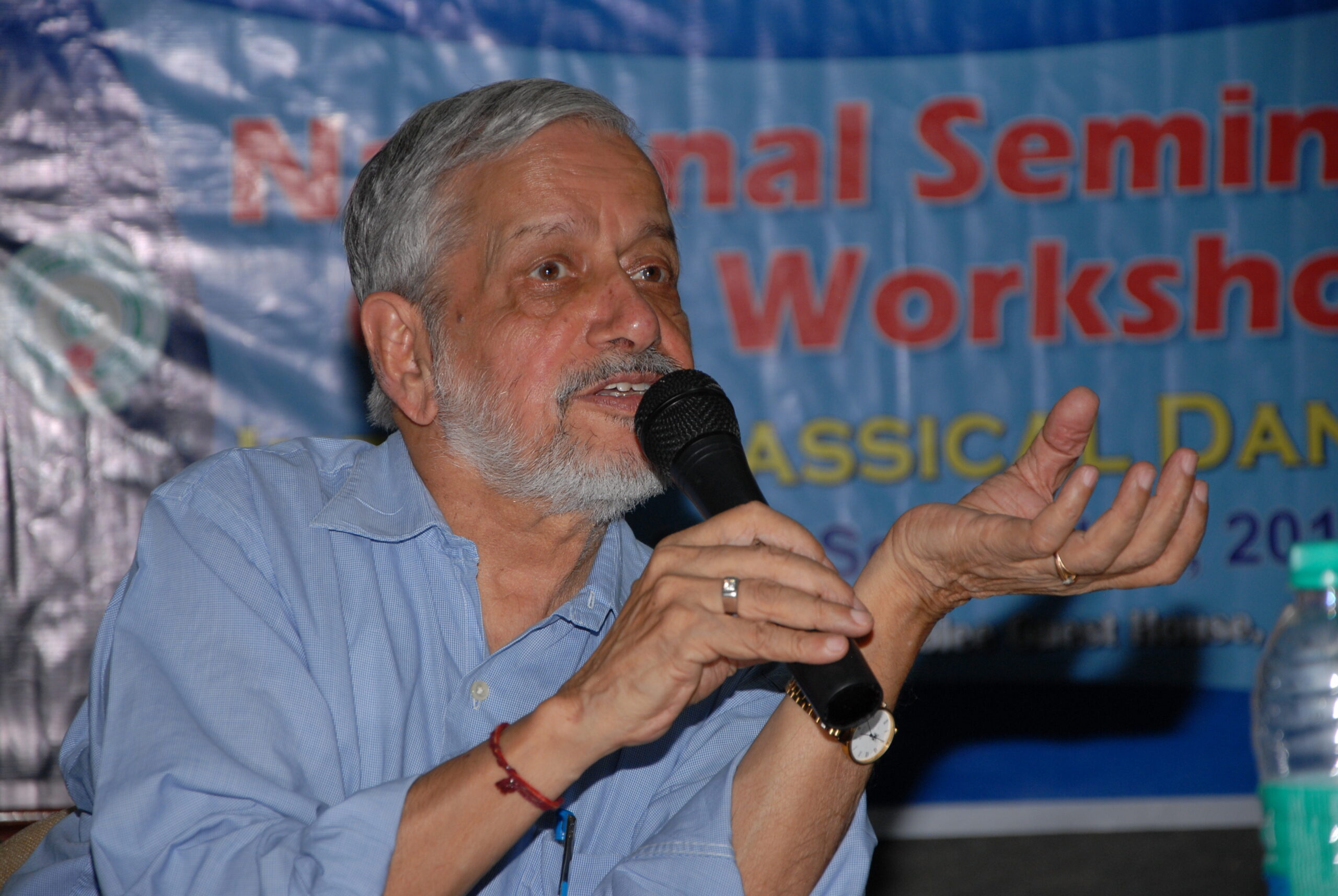

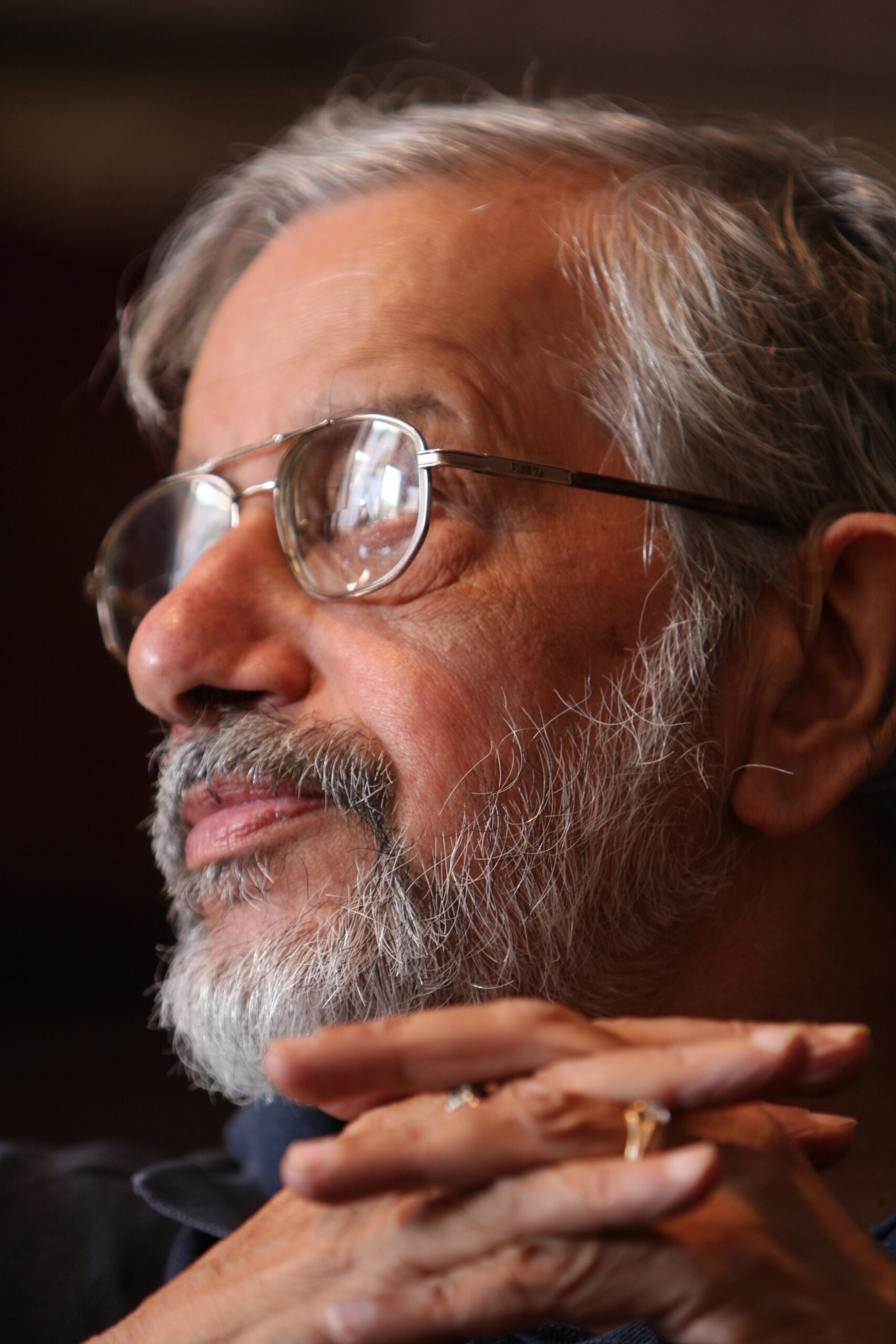

Avinash Pasricha: An Icon in Performing Arts Photography

Text: Paul Nicodemus

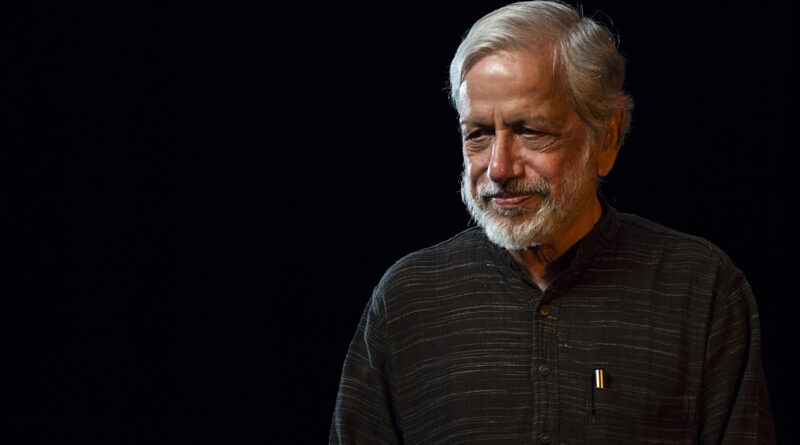

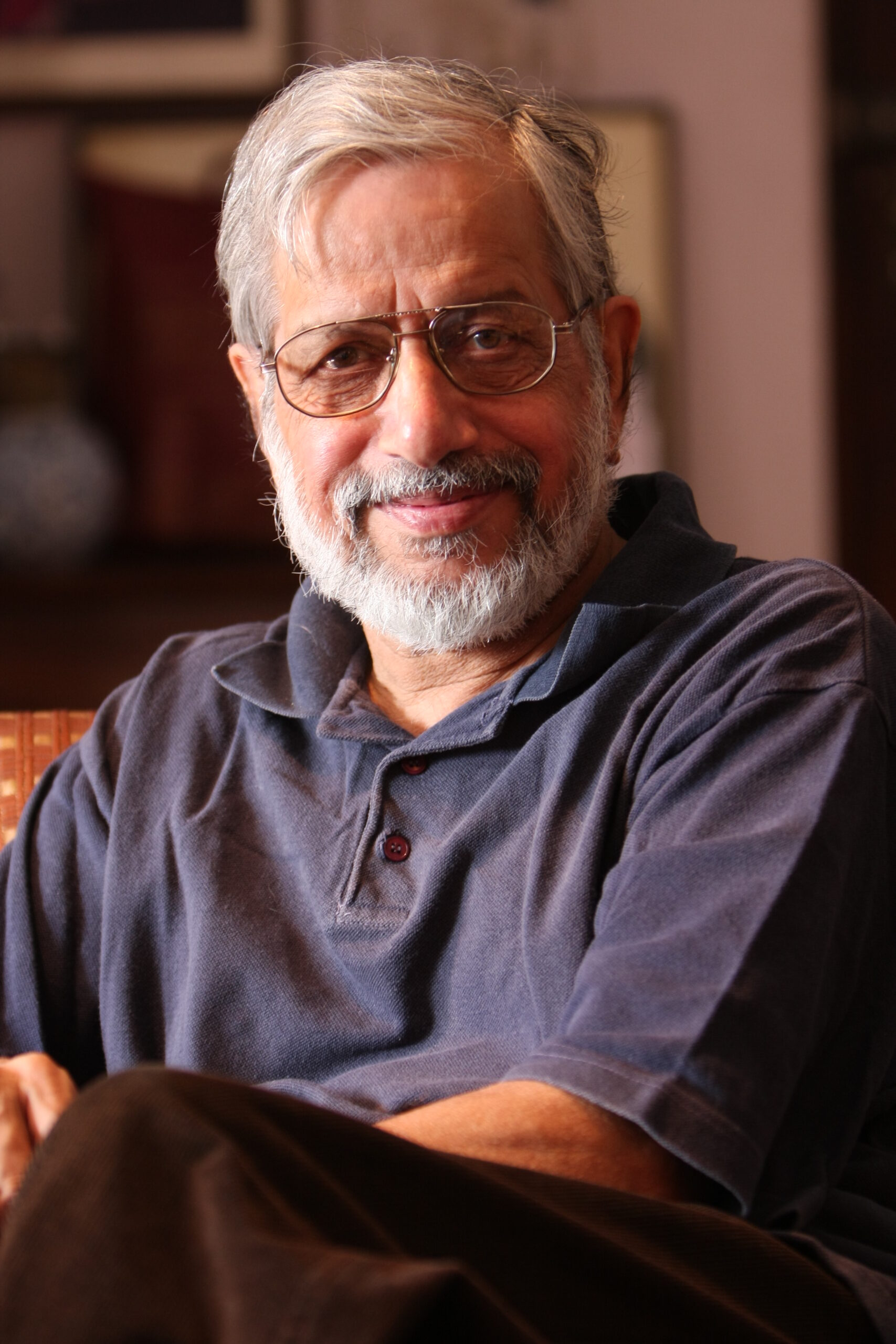

Even after photographing millions of pictures in a career spanning over 60 years, legendary photographer Avinash Pasricha just lights up and beams with energy to discuss photography, performing arts and how he photographed some iconic artistes of India. Going through the photographs on his laptop the octogenarian reminisced and relived those moments.

Avinash is a living legend who has documented performing artistes over a generation and it is hard to visualise Indian art and culture without his work. He has covered the whole range of photography from photojournalism, portraits, fashion, advertising, industry and architecture. He has specialised in performing arts photography since the 1960s.

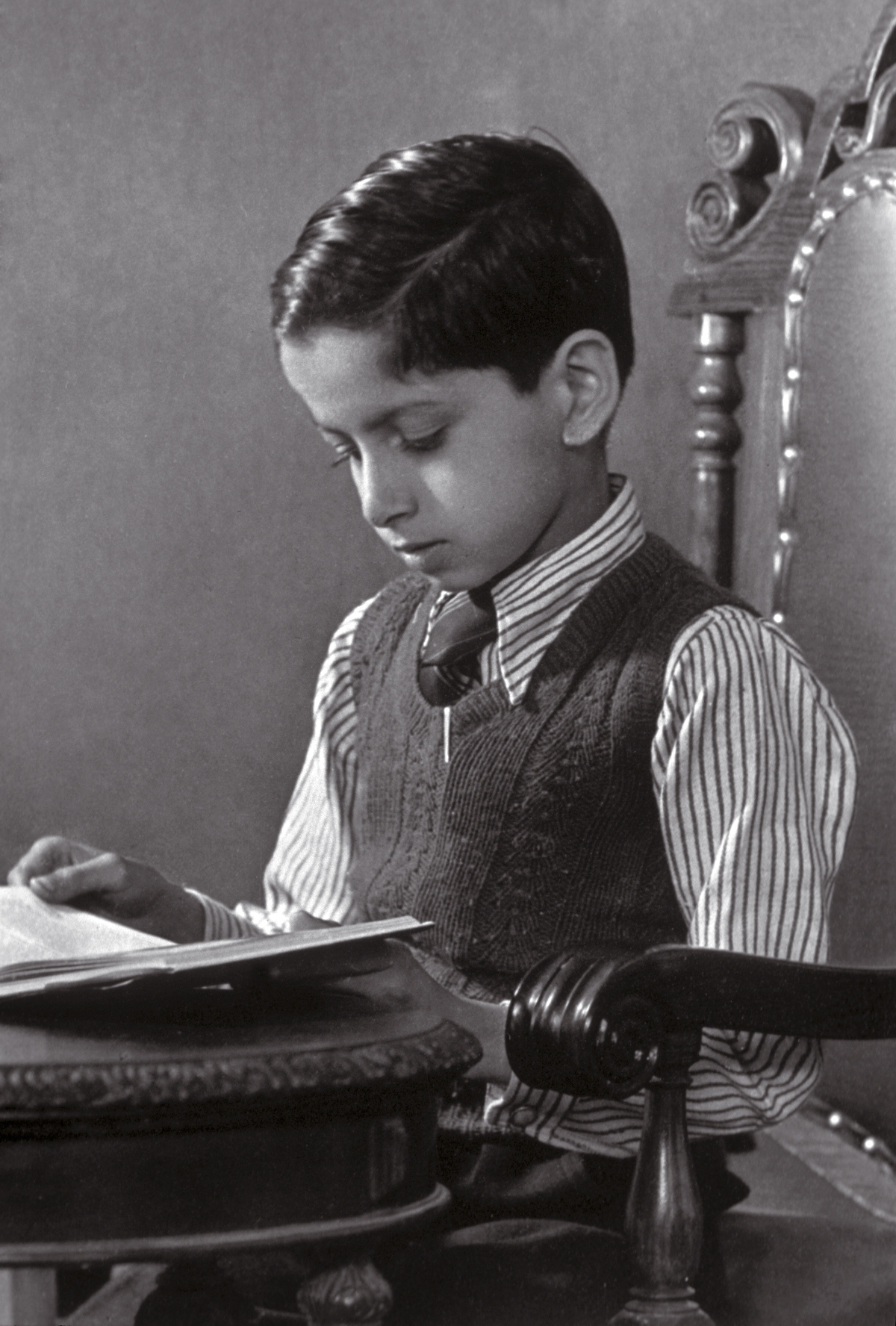

Avinash was born to a photographer father in Shimla on August 2, 1936. His father worked for a company during the British Days, so the family moved from Delhi to Shimla every summer.

It was in 1938, his father opened his own shop ‘Delhi Photo Company’ at Janpath in Delhi and Avinash literally grew up in the studio. He got a chance to notice photography right from his childhood. Then they had a branch in Mussoorie. They went to the hill station every Summer. He did most of his education at Vincent Hill School in Mussoorie. He then attended St Stephen’s College in Delhi and completed his Bachelor’s degree.

Talking about his initial idea of photography he says, “I cut a hole in the paper box, made a pinhole and pasted a tissue paper at the back and kept it around so you can see an image upside down. That was my first idea of photography that a pinhole can form an image.” His father gave him a brownie reflex when he was 10 years old. He used to look forward to becoming a businessman.He used to sit at the counter of the shop in Delhi and in Mussoorie. Then he used to sell pictures to his classmates.In those days, a print cost 4 annas, and he sold it for 8 annas, that was business.Right after college at 20, he joined United States Information Service (USIS) in 1957.

He got into the organisation because one of his father’s friend was starting a photo lab and he looked at it as a great opportunity to learn. After joining, he was partly in charge of the lab and he learnt the art of getting prints made. In 1960, he got selected as the Photo Editor of SPAN magazine published by USIS in New Delhi. The first cover of his work appeared in January 1961. “I became known as a photographer when I worked for SPAN. It was quite an experience to see your pictures in print.” Those days SPAN was one of the few pictorial magazines in the country, printed on art paper. People looked forward to the magazine. He was Photo Editor of the magazine for 37 years. He became an iconic name in the world of photography, his most celebrated body of work is the journalistic work he did for the magazine from 1960 to 1997, including four visits to the U.S. to cover the official visits of Indian Prime Ministers

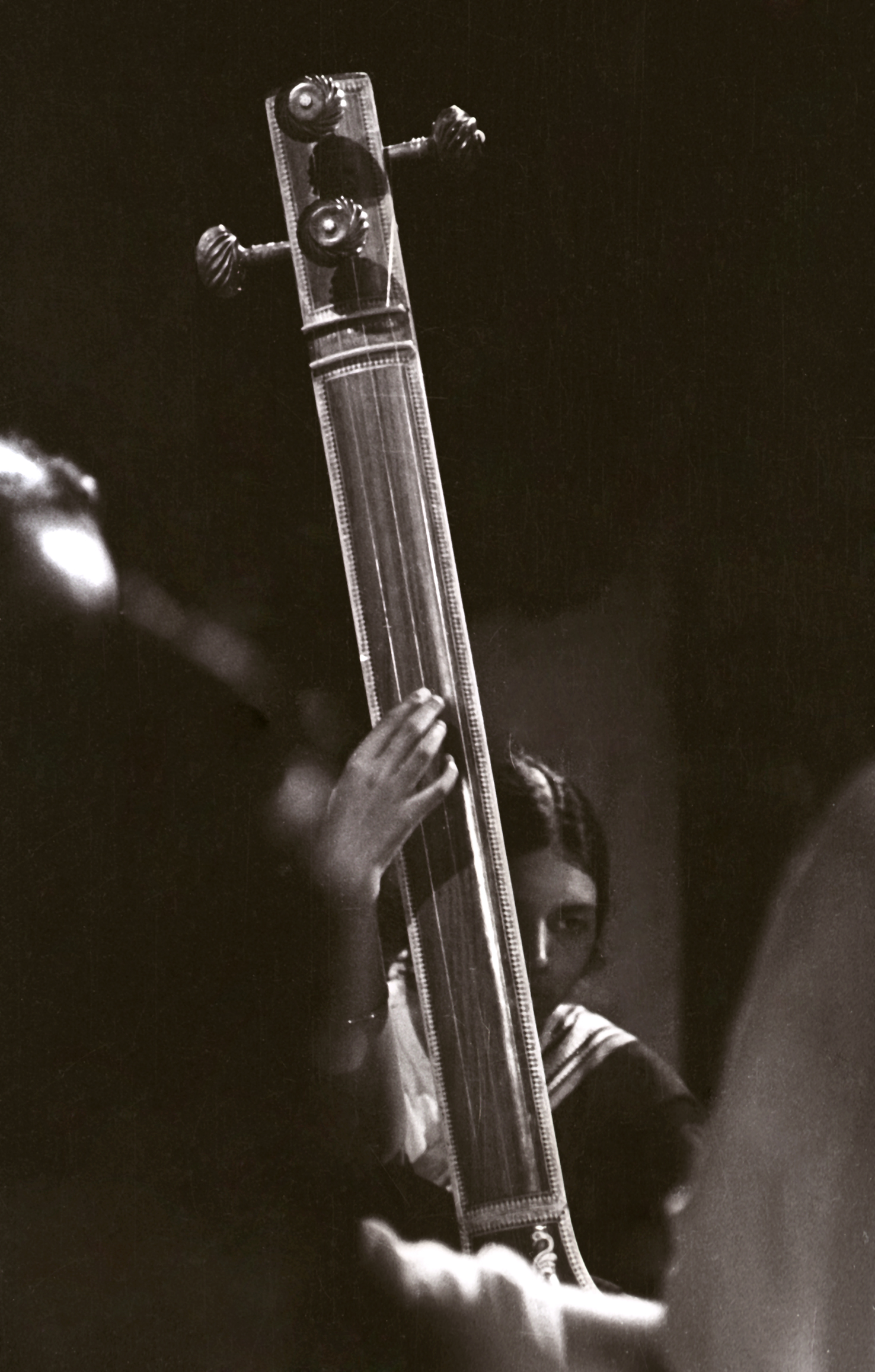

His performing arts photography journey started with music and not dance. In 1966, someone asked him to photograph a festival at Sapru House. “To be honest, photographing performing arts came purely by chance. Somebody challenged me, he said, why don’t you cover a 4-day music festival. I went to the festival, I did not have any ear for music but I had a desire to capture the mood. I got some beautiful shots,” he reveals. That was also the first time he took pictures without flash, to capture the mood with the available stage light, pushing Tri-X from 400 to 1200 and processing in Acufine. That was the start of his beautiful journey. The picture that started him off to music and dance was a girl playing tambura. Her face not visible, a ray of light falling just on her hand. It captured the mood and won him his first prize in a photo competition.

Avinash kept learning and the photo editor job helped him to travel around the country. “The writer may collect the information and write it later but being a photographer I had to produce a picture on the spot which might become a cover or at least a double spread or an illustration. You have to start thinking about how to compose a picture. So the whole thinking process was with no learning and attending no classes. It was learning by doing. It was the same with music and dance,” he says. He explains that the trick is to pay whole attention and focus your mind. Even now he loves seeing a dance performance through his camera than without it. From his experience, he learnt that camera, not only focuses for the picture but it also channelizes your mind towards what is happening in front. “If you are just listening to music and dance, your mind wanders. It is all about focusing your mind to see,” he says.

Everybody loved those pictures, and he continued shooting increasingly. He photographed for Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, an institution for classical music and dance in New Delhi and gradually moved from photographing music to dance. He enjoyed capturing the mood of the artistes. Those were the days of Rolleiflex cameras. “We had two Rolleiflex cameras, one for colour and the other for black and white. That was an expensive and complex camera of those days with two lenses. 35mm cameras came later. The story of performing arts started because of Acufine, black and white and capturing mood instead of using flash,” he reveals. The first four rolls that he shot in 1966 were made into prints and everybody loved them because people in India were not used to seeing such pictures of mood, light and shade.

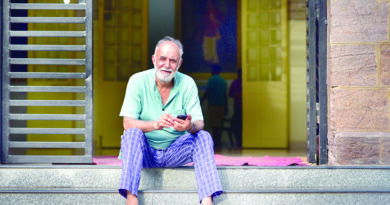

He got married in 1963 and his wife comes from Punjab. “It was a family-arranged affair. She was interested in music and learnt music. Her interest in music and my interest in photography still continues,” he says. The advantage of working with USIS was that the office closed at 5-30 pm and it was at a walking distance from his home. He was free by 6 pm to attend concerts. “We don’t want to sit at home, two of us,” he smiles. For the last several years, since he retired, they have been going to a concert every day of the week.

Avinash had been a film shooter for most of his career and it was only in 2006 he shifted to a DSLR. When asked, if he found any difference? His answer was both yes and no. Initially, he was not happy with the digital SLR because the first camera he had, had a time lag, plus it wouldn’t do multiple images then. It was a Canon D40 which he still has. For him, the film shoots the moment and in digital, you might miss the moment. One disadvantage of digital cameras is that you overshoot. For a half an hour programme you shoot you have to come home and spend two hours on the computer to edit – what to keep and what not to keep. The advantage is that you can right away see what you are getting. For the last eight months, he has been scanning the negatives he shot over the years. “So far, we have gone through negatives from 1966 to 2004. We are planning to index all the useful photographs,” he says.

He realises that age is catching up and wants to give his body adequate rest. “Now my shoulder is giving way and I can’t carry heavy lenses. So I bought myself a tiny Panasonic, and it has been doing the job for me,” he says. He has reduced his shooting and says the dichotomy he faces is whether to carry the camera or not to carry the camera.

After decades of capturing, he has whole life histories of popular musicians and dancers and he could do a pictorial biography of many legendary artistes. He has made audio-visuals on music, dance and prominent performing artistes like MS Subbulakshmi, Begum Akhtar, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Kumar Gandharva, Pandit Shambhu Maharaj and on Odissi, Mohiniattam and Bharatanatyam. Recollecting the last AV he made on MS Subbulakshmi he says, “She was being given a Lifetime Achievement Award in Delhi but she could not come down. So, I went to her house, and she sang for me for a whole half an hour. After I finished, she made a Dosa for me,”. It was a memorable moment for him.

Skimming through the photographs on his laptop, he recollected experiences of photographing some legends. Showing the photograph of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra he comments, “Kelu babu, I love him, there is a certain feeling this person has, which he puts into his performance, no female can quite pose like him.” Looking at the photograph of legendary dancer Balasaraswati he says, “Bala, there is a story about her, I was assigned to go and shoot and within 7 to 8 shots, Indrani Rehman walks up to me and says, ‘she has indicated me, so don’t shoot.’ I was very angry, I was young those days, I just walked out of the hall. After that I went to her house, she wouldn’t do anything, sat in her armchair in the veranda. I shot two rolls and got a nice expression out of her and we used a picture for SPAN,” he reveals. Today, those are the quality pictures of Balasaraswati that remained. How we wish he shot more pictures of her.

He has photographed with deep sensitivity and diligence, India’s greatest legends in the world of dance and music. Today, he has the largest personal collection of rare and enduring images of India’s greatest performing artistes. He received the Sangeet Natak Academy Award 2016-2017 and the Natya Vriksha Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

His photographs have appeared in many prestige publications in India and abroad, including Life and National Geographic magazines. They have also been published in books on India published by the Festival of India. The MEA used several of his photographs in the Millennium Book on New Delhi. In 2000, he and his son Amit photographed the Supreme Court buildings for a coffee-table book—’The Supreme Court 1950-2000’. In 2002 both collaborated in a book on the Rashtrapati Bhavan entitled “Dome Over India” and in 2005-06 in a book on the Raj Bhavan Nainital entitled “A Scottish Castle in Kumaon Highlands.” Amit is now famous for his panoramic work in a book entitled: “Monumental India”, “The Sacred India Book” and “India At Home”. Avinash has been a regular contributor for The Dance India magazine since 2016.

He has co-authored books on Indian dances, Odissi, Kathak, Kuchipudi and Sattriya with Dr Sunil Kothari and one entitled ‘Rhythm in Joy’ with dancer/writer Leela Samson. A large coffee-table book ‘Indian Classical Dance: Tradition in Transition’ co-authored with dance critic Leela Venkataraman was published by Roli Books and was widely acclaimed. He co-authored a book on Pandit Kumar Gandharva with writer/critic Raghava Menon. Several of his dance pictures have been used in various publications, calendars and in advertising. Three picture pocketbooks on Kumar Gandharva, Pandit Birju Maharaj and Guru Kelucharan. Plus Wisdom Tree published seven small books co-authored with different dancers and edited by Alka Raghuvanshi in 2004. A book on all styles of Indian classical dance co-authored with Sonal Mansingh, and one on Indian Classical Music co-authored with Debu Chaudhuri was published in 2007 in the Incredible India series. He has had four exhibitions of his dance and music pictures in galleries and auditoriums in Delhi, Chennai, Patna, Varanasi and Toronto.

The Pasricha Gharana in Photography continues with brother Kiron, nephew Ravi and son Amit, all doing photography. Another son Veenu is a specialist in computer graphics, audio-visuals and multimedia shows. The family has made multimedia CD-ROM Audio-Visual Productions on “Delhi-The Eternal City” for South Asia Tourism and Travel Exchange (SATTE) conference in Delhi and one on India Tourism entitled “SHE” for tourism promotion in the United Kingdom.

His message to the upcoming dancers and photographers, “Dancers, please dance with bhav visible through your eyes. If the bhav is visible through the eyes, then it is worth capturing. If it is just movements without inner involvement, then it doesn’t come through. Photographers shoot dance poses rather than the dance through the eyes. Eyes are the most significant feature of dance photography. Even when they are closed, they convey an expression.”

“I love my profession, it lets me see, look at life, look at people, walk into factories, institutions, travel, become curious about people, about life, to develop a feeling of empathy,” he concludes.