Shashadhar Acharya: The Chhau Maestro

Text: Paul Nicodemus

He has played an immense role in the evolution and development of Chhau, a traditional dance-theatre art form of India. His devotion made him a consummate performer, a devoted teacher and an exemplary artiste. Guru Shashadhar Acharya is an eminent exponent and choreographer of Chhau Dance of Seraikella. He has often stretched his knowledge to use the technique in innovative ways both in dance and theatre. He is a Chhau Maestro.

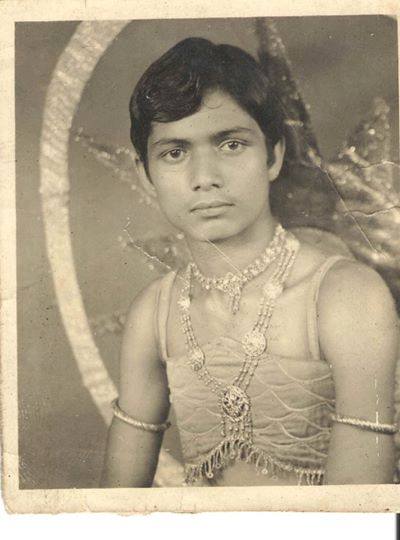

Shashadhar Acharya was born on May 5, 1960 in Seraikela under Singhbhum Dynasty in Jharkhand into a family of traditional performers. He is the fifth generation dancer and his son Shubham Acharya has become the sixth generation dancer of the art form. “I was born in Seraikela, from where the art form Saraikela Chhau got its name. Now, it is in Jharkhand but previously it was in Bihar and before that in Odisha. So basically we are Odia people,” he says.

Shashadhar has been attached to the art form since his birth and started dancing quite early in his childhood. There has always been activity related to dance around him. At the age of 6, once he got awareness, he requested his father to teach him to dance. His father agreed and asked him to join the class along with other students and never taught him separately.

Though he was initiated into Chhau dance by his father Lingaraj Acharya, he went on to learn the art form from five other gurus. He continued his training under Natashekar BB Pattanaik, Padma Shri awardee Siddhendra Narayan Singh Deo, Vikram Kumbhakar and Padma Shri awardee Kedarnath Sahoo. He has also studied the Chhau dance of Mayurbhanj under Alok Niranjan Bisoi and has had training in Dhol-playing under Surmukhi. His father never objected him from learning. “Earlier, we had to learn rhythm, swara, movement and many other things. Now things have changed, but I learnt in Guru-shishya Parampara. In that tradition, some people only dance two or three items till the end of their careers. But our generation is different, we learnt to play both male and female characters and much more,” he says.

His father asked him to go everywhere and learn and then think about Chhau. He learnt simultaneously from different gurus at different times of the day. “All of them knew I am learning from the other guru but I never told them. They loved me because right from my childhood I was passionate about Chhau,” he says.

He was associated with theatre and dance from his childhood. He stood first in every cultural competition at his school in Seraikela in singing, dance and drama. “Everybody born in Seraikela has Chhau in them,” he says.

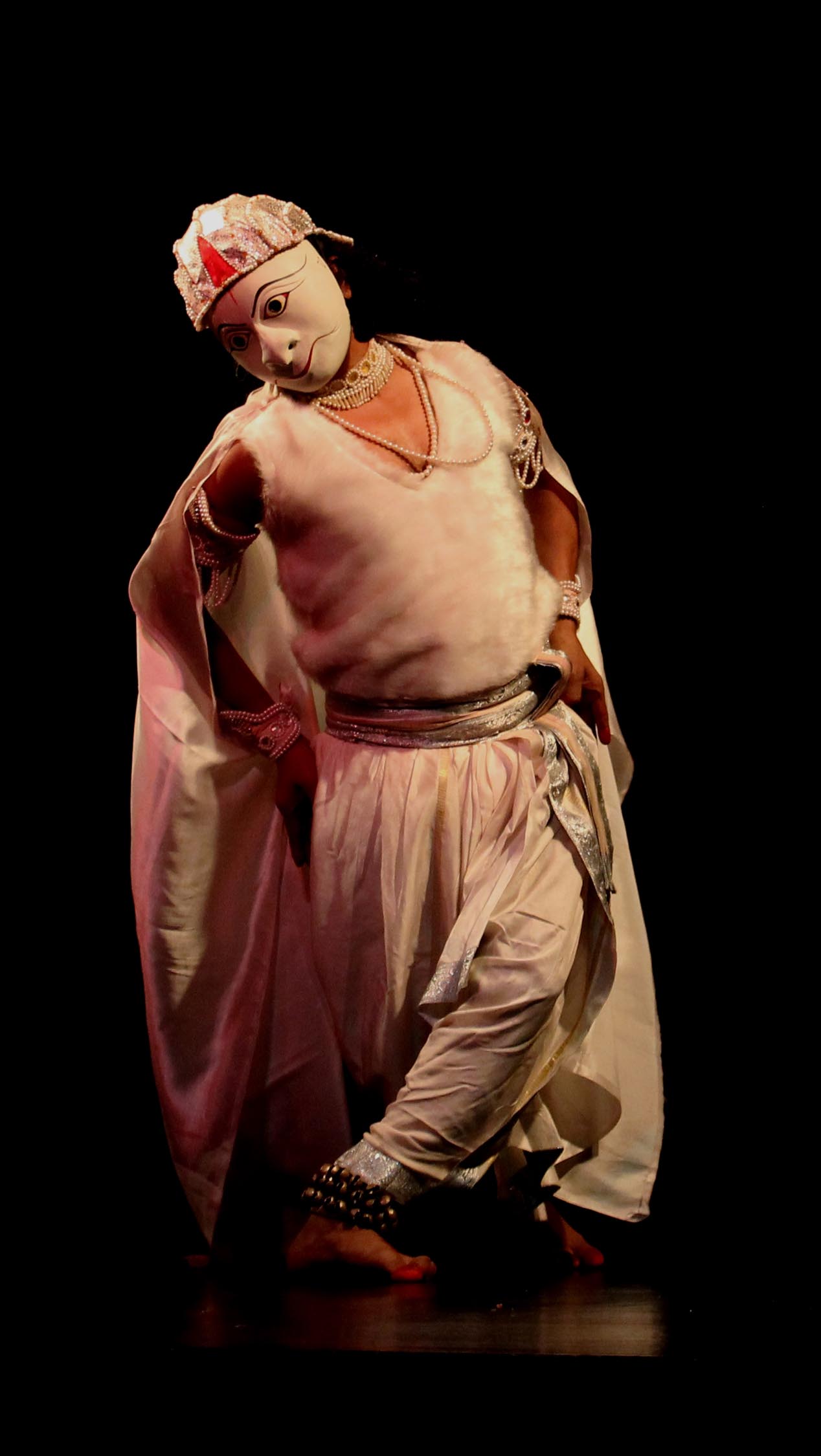

Earlier, performers of Chhau were restricted to two or three items. According to them the physical appearance of the character mattered and they believed that not everyone can play every character. Characters were portrayed only if they suited the artiste. “Now, we have aharya and even if I do not look like Ravana, I can make myself look like Ravana with the help of ornaments and makeup,” he elaborates. In 1974, one of his gurus died, and he started learning Indian Combat techniques from Guru Vikram Kumbhakar. The art form of Chhau draws its technique from Indian Combat Arts, Bharatiya Yudha Kala.

Shashadhar Acharya gave his first performance around the age of 12 years in Chaitra Parva, the annual festival of Chhau in Seraikela. It was his Manch Pravesh. After that, he ventured out to perform at varied venues. The earlier tradition saw accomplished students of Chhau perform at Chaitra Parva in front of the people of Seraikela after getting a nod from their guru. The people of Seraikela certified the performer. But now, the teaching and schooling system is different. Earlier, guru would call for a practice at any time of the day. There was no fixed time. Learning was more practical than theoretical. “Earlier, gurus would give a concept and asked the disciple to think over it, instead of spoon-feeding them. ‘Today, you think about it and share your experience, and tomorrow, I will share my experience,’ was the system,” he says. It gave him ample scope for improvisation.

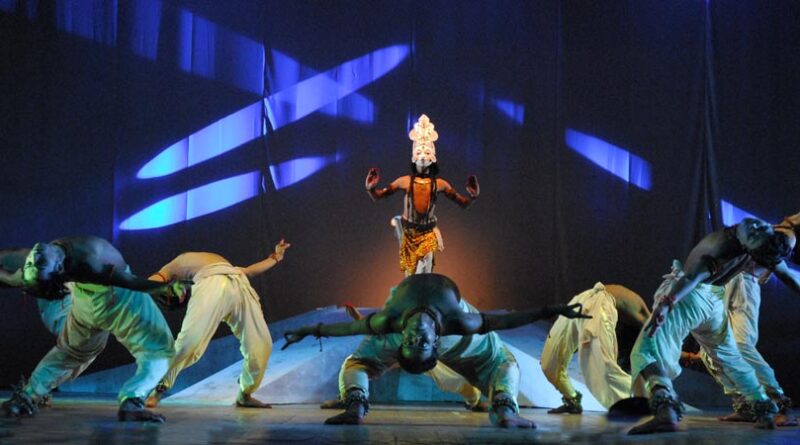

Seraikela Chhau is an art form different from all the other art forms of India. Some art forms have started from temples, some from a king’s courts and some from festivals but this art form started from a Military Cantonment. “In the beginning, we train as a soldier. The total body language would be of a soldier. But when we dance, it is different. If I perform Bharatanatyam, Odissi, Manipuri or Kathak, people will see me doing Krishna or Radha. But because we use the mask in Chhau, I lose my identity on stage and get the identity of the character. I am not against any art form, I am just speaking about my art form,” he says. Chhau literally means mask in Odiya. The combative movements of attack and defence mixed with an imitation of animal, bird movements and daily household work brought into the theatre and dance became Chhau.

The most prominent difference among the three subgenres is the use of masks. While the Seraikela and Purulia styles of Chhau use masks during the dance, the Mayurbhanj Chhau uses none. “Before the 19th century, Chhau was a single art form, and it did not have various styles. After 1947, the region of Chhau was divided into three states — Bengal, Odisha and Bihar. Purulia performers in West Bengal are still farmers, Mayurbhanj had performers from a lower caste and got rid of the mask,” he says.

Chhau does not have a verbal language but has a body language. And body language is a universal language. “We have a great chance of going abroad because Chhau does not have a language. You can throw me anywhere and I will perform,” he smiles.

In 1987, Shashadhar moved to Mumbai and worked as a teacher. During his stay at Mumbai, Veenapani Chawla, popular art director, asked him to choreograph an English play with Chhau movements and he did. They staged the play at Prithvi Theatre and Ratan Thiyam, the then director of the National School of Drama (NSD) and Dr Suresh Awasthi, chairman of NSD happened to attend it. After the show, they enquired about the choreographer and came to know about Shashadhar. They gave him an opportunity to come to the National School of Drama and he moved to Delhi in 1988. “Initially, I thought I would get an admission at NSD but when I went there, I was asked to teach the second-year students. Since then I have been teaching,” he says.

Shashadhar has done extensive research in Chhau which is believed to exist from 1200 AD. He iterated that the teaching method has always been oral and nothing was in the written format. When he realised it, he has focused on the teaching method. The survival of a tradition depends on its transition from one generation to the next and contributing towards its continuity is the responsibility of every practitioner of a traditional art form. Shashadhar Acharya teaches with a passion. Devoting a large part of his time to teaching, he nurtures each student to develop as an artiste while respecting the tenets of tradition.

Performing Chhau runs in his blood. He never wanted to enter the field of dance but did so because of circumstances. Apart from his general studies, he is a graduate in literature and has completed law. He gave up three jobs – two central government and one state government — to freelance. “One of the best things to happen in life was that all my four brothers and my son are with me and we have been performing Chhau together. It is a great thing,” he says.

When he left Seraikela, teaching dance to students and forming his own dance troupe was on his mind. But when he approached dance institutions looking for teaching opportunities in Delhi, they told him he was too young to teach. Upon knowing about Shashadhar’s father, Dance Institutes in Delhi asked him to call his father to teach in Delhi. He says his father came down to Delhi and stayed with him for a year. In the meantime, Shashadhar prepared his ground.

He has been performing for the last 40 years and has given over 3000 performances in 75 countries. Apart from performing, he also gives lec-dems and seminars. “At present, I am doing something interesting. I am associated with theatre and teaching on how an actor should have a disciplined body and what needs to be done for a disciplined body,” he says. He has been teaching at the National School of Drama and Film Institute.

For him, there is not much of a difference between theatre and dance. “Theatre has dialogue and dance does not and all the other things are similar — space, timing, design, lights,” he explains. The deep-rooted knowledge of his art gave him the confidence to use it in collaborative works with dancers, actors and directors of both traditional and modern discipline.

He served as an expert in various committees for selections of scholarship, fellowship and other awards in Chhau dance. He also served as an expert for the film production on Chhau for several organisations.

For his sustained and innovative work in Seraikella Chhau, Shashadhar Acharya has received many awards including the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award; Rajkiya Samman by the Government of Jharkhand; Guru Dev Prasad Das Samman by Government of Odisha; Lifetime Achievement Award and Jharkhand State Samman by Government of Jharkhand; Unity in Diversity PhD Art & Culture Samman in PHD House, New Delhi and Natyashree Award by Nataraj Music and Dance Academy, Visakhapatnam. He has performed in over 75 countries at Festivals of India and other major Theatre Dance festival in Asia, Europe, USA and Africa.

Shashadhar Acharya teaches at Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi. He has established Acharya Chhau Nrutya Bichitra in Seraikela for the promotion of Chhau dance in Jharkhand. The institution houses a library and a museum displaying articles on Chhau dances. He has trained both students of dance and theatre for the last twenty-five years and has been responsible for bringing Chhau to New Delhi. He also heads a project funded by Central Sangeet Natak Akademi to train dancers for creating a performance repertory based in New Delhi.