Article: KATHAK

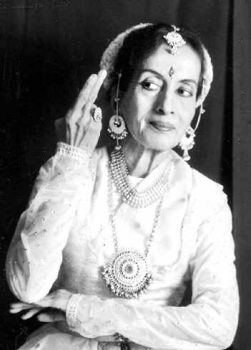

Dr. (Smt.) Kanak Rele

Padmabhushan, Akademi Ratna (Fellow of Sangeet Natak Akademi)

Director, Nalanda Dance Research Centre

Kathak, the classical dance style from North India conjures up visions of scintillating footwork and lighting ‘chakkars’ that is the pirouettes. The word ‘Kathak’ is derived from the word ‘Katha’, which means a story. In ancient times, the wandering bards called ‘kathakars’, used to go from village to village and recite predominantly, the two epics of Hinduism ‘Ramayana’ and ‘Mahabharata’. During the Muslim invasions, the Persian influence also came into the art brought in by the dancing girls who were called ‘tawayafs’ which was a spiritual dance, and slowly started turning into a court presentation. Today, what we see in Kathak is a blend of these two streams.

In order to make their art more attractive, these Kathakars inculcated a sense of rhythm and step to their recitals to communicate stories through rhythmic foot movements, hand gestures, facial expressions and eye work. It has got the courtly atmosphere along with being highly spiritual.

A practice which started in the earlier centuries of the Christian errand was a simple form of expressional dance evolved into a distinct style in the l5th and 16th centuries with the popularization of the Radha-Krishna legend and the emergence of Madhura Bhakti, a special manifestation of Vaishnavism. This emergence of Madhura Bhakti gave rise to an operatic play called Rasa-Leela, which developed mainly in the Braj areas associated with Lord Krishna’s early life. This Rasa-Leela gradually developed into a well established folk theatre which had a harmonious blend of song, storytelling, acting and dancing.

With the advent of the Muslim rulers, Kathak turned into a court dance from a temple dance. This resulted in two different styles, where one style of dance was on the Hindu patronage in the court of Jaipur and the other with the support of the Muslims, Courts of Delhi, Agra and Lucknow. Yet, in both these styles Kathak was treated as a solo art, where the touch stone of excellence was the virtuosity of the solo dancers, especially their command over ‘laykari’ of footwork.

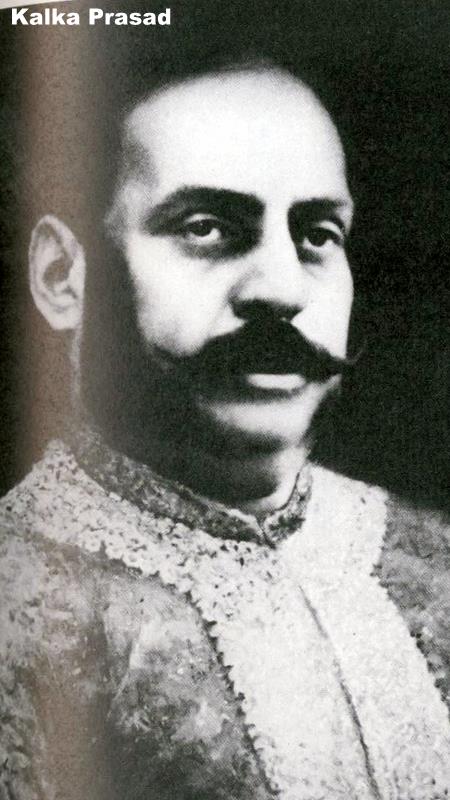

In the Jaipur court style, the emphasis almost totally shifted on the ‘nritta’, making the style, a vehicle for mere mechanical display. While the Muslim patrons had no overpowering preference for mere rhythmical pyro technique; they fancied an art that was full of human sentiments and worldly situations. Thus, their brand of Kathak stressed on ‘nritya’ filled with ‘bhaava’ making Kathak, more graceful and sensuous. This style was recognized as the Lucknow Gharana and it came into existence during the rule of Wajid Ali Shah. The chief architect was Thakur Prasad, whose two sons Kalka and Binda Din perfected it.

Another noteworthy patron of Kathak was Raja Chakradhar of Raigadh in Madhya Pradesh. He encouraged both the Lucknow Gharana’s and the Jaipur court performers. He too was then disregarded by the British for his great love and lavish spending on Kathak. Though the great votaries of Kathak were majorly men, women also had a place in, Kathak, although it was quite dubious, their contribution in the early part of development was not significant. These women divested their dance of any dignity and came to be termed as women of easy virtue.

Wajid Ali Shah’s contribution to development of Kathak is noteworthy. He was an accomplished dancer, a musician and good poet in Hindi and Urdu. He spent lavishly on dance and music, much to the disgust of the British of the East India Company, who dethroned him and exiled him to Calcutta and annexed his principality ‘Oudh’. Until his death; Wajid Ali Shah lavishly spent his pension on Kathak and music.

As Kathak is popular both in Hindu and Muslim communities the costumes of this dance form are made in line with traditions of the respective communities. There are two types of Hindu costumes for female dancers. While the first one includes a sari worn in a unique fashion complimented with a choli or blouse that covers the upper body and a scarf or urhni worn in some places, the other costume includes a long embroidered skirt with a contrasting choli and a transparent urhni. Costume is well complimented with traditional jewellery, usually gold, that includes the ones adorning her hair, nose, ear, neck and hand. Musical anklets called ghunghru made of leather straps with small metallic bells attached to it are wrapped in her ankles that produce rhythmic sound while she performs excellent and spectacular footwork. Head jewellery adorns her in the second case. Vivid face make-up put on helps highlight her facial expressions. Hindu male Kathak dancers usually wear a silk dhoti with a silk scarf tied on the upper part of the body which usually remain bare or may be covered by a loose jacket. Jewellery of male dancers is quite simple compared to their female counterparts and are usually made of stone.

The costume for Muslim female dancers includes a skirt along with a tight fitting trouser called churidar or pyjama and a long coat to cover the upper body and hands. A scarf covering the head compliments the whole attire which is completed with light jewellery.

Kathak originally had only two instruments, the sarangi and the tabla. To large extent the Kathak technique is ‘nritta’ oriented and concerns itself with rhythm and timing. Due to this, the footwork is the predominant element of Kathak. The dancer ties atleast 100 ‘ghunghroos’ on each foot and cajoles myriad rhythmic patterns, nuances and tonal variations by the footwork which is called ‘tatkar’. It is amazing that a versatile dancer can sound only one ‘ghunghroo’ out of the full complement of 100 ghunghroos in the most melodious manner. A complete unit of nritta has not only scintillating footwork, but also an accompanying, harmonious use of the entire body. Such a piece is called a ‘toda’ which has several varieties. This exhibition of todas is the true test of a Kathak dancer’s dexterity and virtuosity.

Another notable facet of the Kathak nritta are the chakkar or the pirouette or spin which are performed at a lightning speed and which end in a superbly balanced flourish and pose. The nritya in Kathak has two types of Gat, Nikas and Bhav. Out of these the Gat-Bhav is full blown nritya depicting a theme, a story or an episode. In comparison to the other more developed dance styles, Kathak has a very few hasta mudras, that is the palm depictions. Thus, for emotive passages the attitude of the body and the different stances it adopts to depict an idea is used in the most effective manner. For example, the Ghunghat Gat which is supposed to depict unveiling of the ghunghat (veil) over the face by a woman; the dancer will not do just one interpretative action, but will show different ways in which the ghunghat is unveiled in different situations and moods.

The items for nritya interpretation are the ‘Thumri’ and ‘Bhajan’ which are danced to complete songs with practically no hasta mudras; making the role of the hands secondary. Even the mukhaja abhinaya is very subtle and suggestive, whereas the other items in this genre are the Dadra and the Gazal, which are types of songs to which Bhav-Gat is created. Since originally Kathak was a religious dance, there were religious songs like Dhrupads, Keertans, Dhamars, Horis, Pads which were utilized for depiction of Nritya.

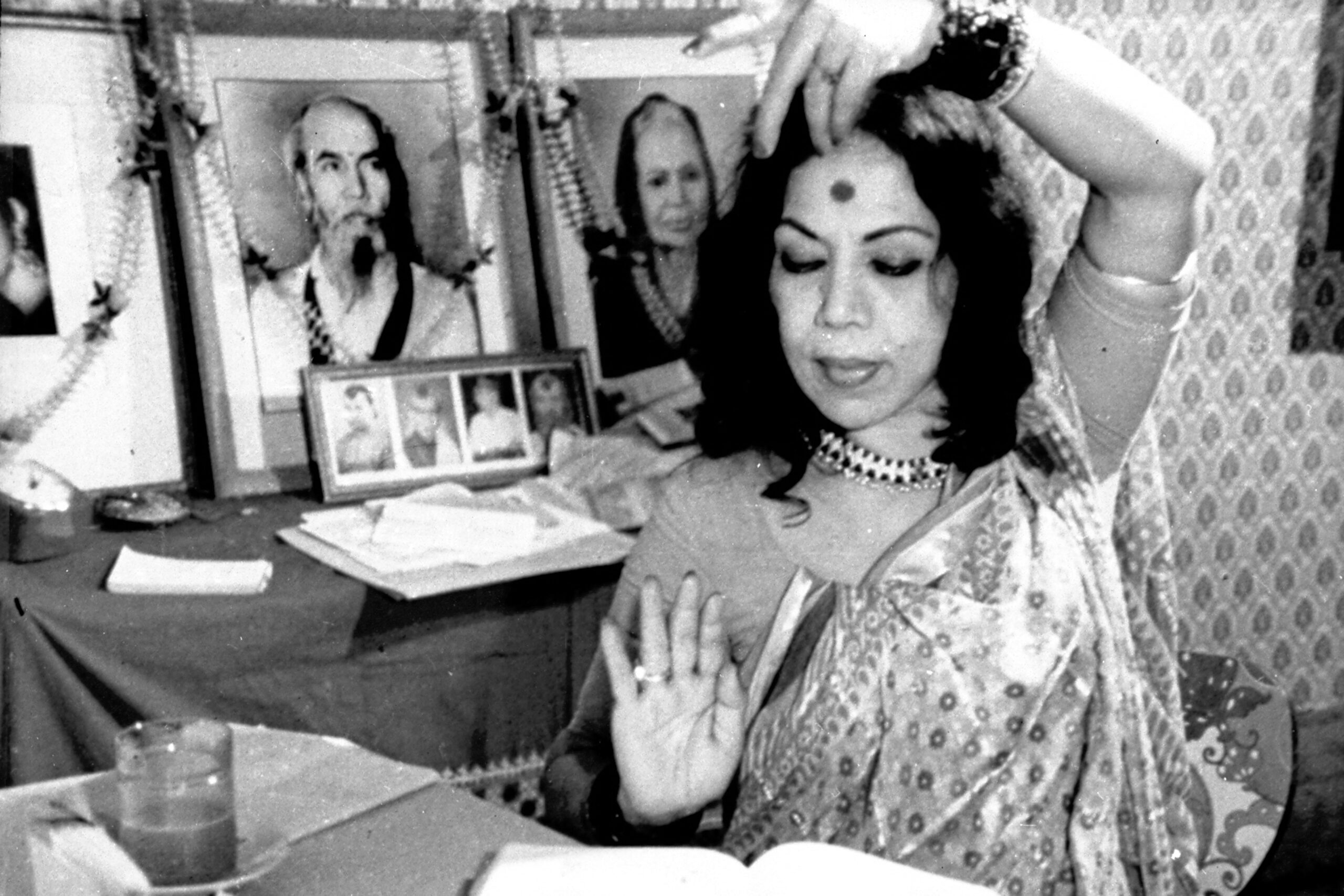

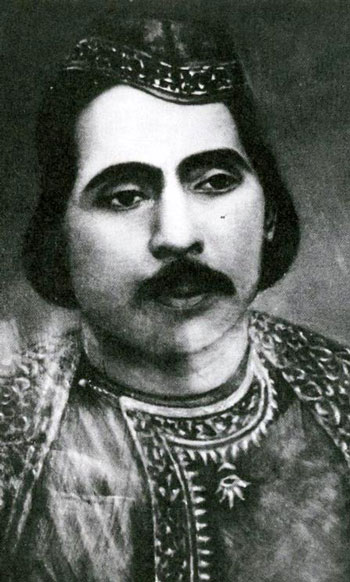

Bindadin Maharaj

Chaube Maharaj

Kalka Maharaj

In the recent times two new items have been added which are the Vandana, a propitiatory item done at the beginning of the recital in praise of a deity, while the Ashtapdis which are taken from poet Jayadeva’s Geeta Govind.

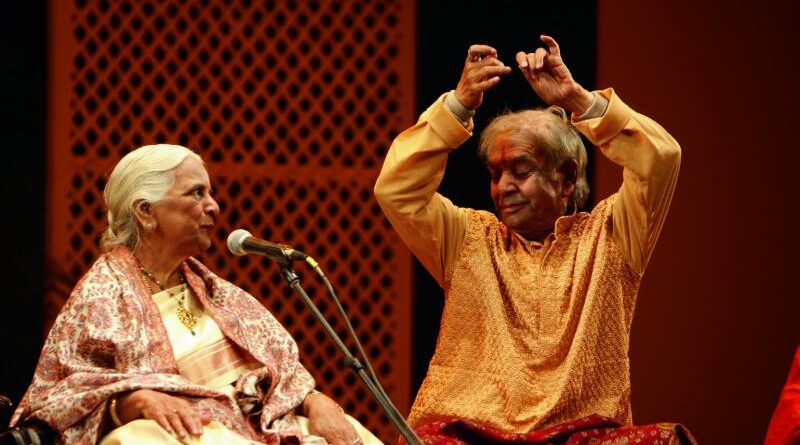

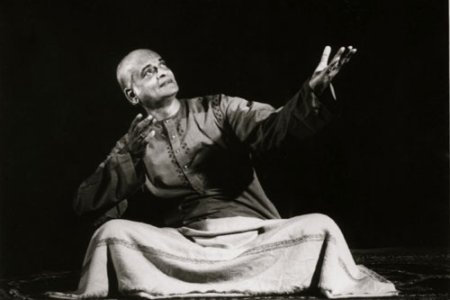

Birju Maharaj

Shambhu Maharaj

Lacchu Maharaj

Today, Kathak has emerged as a distinct dance form. Being the only classical dance of India having links with Muslim culture, it represents a unique synthesis of Hindu and Muslim genius in art. Further, Kathak is the only form of classical dance wedded to Hindustani or the North Indian music. Both of them have had a parallel growth, each feeding and sustaining the other.